Consumer experience and biometrics are at a crossroad as consumers nervously re-emerge

By Vijay Balsarubimaniyan, CEO Pindrop

I recently did something I haven’t done in years: I went for 3 months without getting on a plane. Since I founded Pindrop in 2011, I have been traveling 8-10 times a month. In recent months, like millions of others worldwide, I’ve been indoors, working hard in close contact with my family, observing social distancing to try to minimize the spread of COVID-19.

Now I’m ready to consider re-emerging. But things don’t look the same: when I walk down the streets of Atlanta, I’ll be wearing a face mask and gloves. And I’ll be trying to touch as few things as possible. Every interaction, physical or otherwise, is a risk for infection.

This poses a big issue for consumer experience and the biometrics industry in general. One big change in the wake of COVID-19 is the prolific use of masks in public to prevent the spread. The use of masks becomes problematic when we look at all of the experiences that use facial recognition or touch to interact. It’s clear that face masks pose real issues for facial recognition, which has been taken mainstream by Apple. On a more fundamental level, consumer behavior has become much more cautious: they don’t want to touch things in public, and they’re acutely aware of the health risks. Fingerprint authentication, and even swiping ID cards, are suddenly unnerving experiences.

As a researcher at heart, I wanted to understand how different biometric technology would handle the incorporation of a face mask. Given this, Pindrop’s research team decided to test voice recognition technology to see how it will handle the COVID-19 world. What we found suggests the world may need a lot more Alexa and many fewer fingerprint screens and video/face biometric technology, if we want a rapid return to normal.

This video shows successful authentication of the speaker using short utterances at three different distances (2 feet; 10 feet and 20 feet)

What We Tested (And The Masks)

To determine whether voice recognition is effective in a post-COVID world, Pindrop collected speech phrases from 100 total speakers

Participants recorded themselves using their laptop computers and a web application in two different sessions each: one without wearing a mask and one while wearing a mask of their choice. The masks could be:

- A DIY cloth mask (e.g. using a scarf layered around your face)

- A dust/paper mask

- A surgical mask

- An N95 mask.

Different masks were observed in order to gauge their different effects on the frequency spectrum of voice, and participants were asked to record themselves standing various distances away from the biometric source – up to 30 feet away.

The test used Pindrop’s latest DeepVoice engine for 16 kHz. Each session used up to 20 short phrases (1-2 seconds in length) common for voice application use cases like, “How is the weather today?”

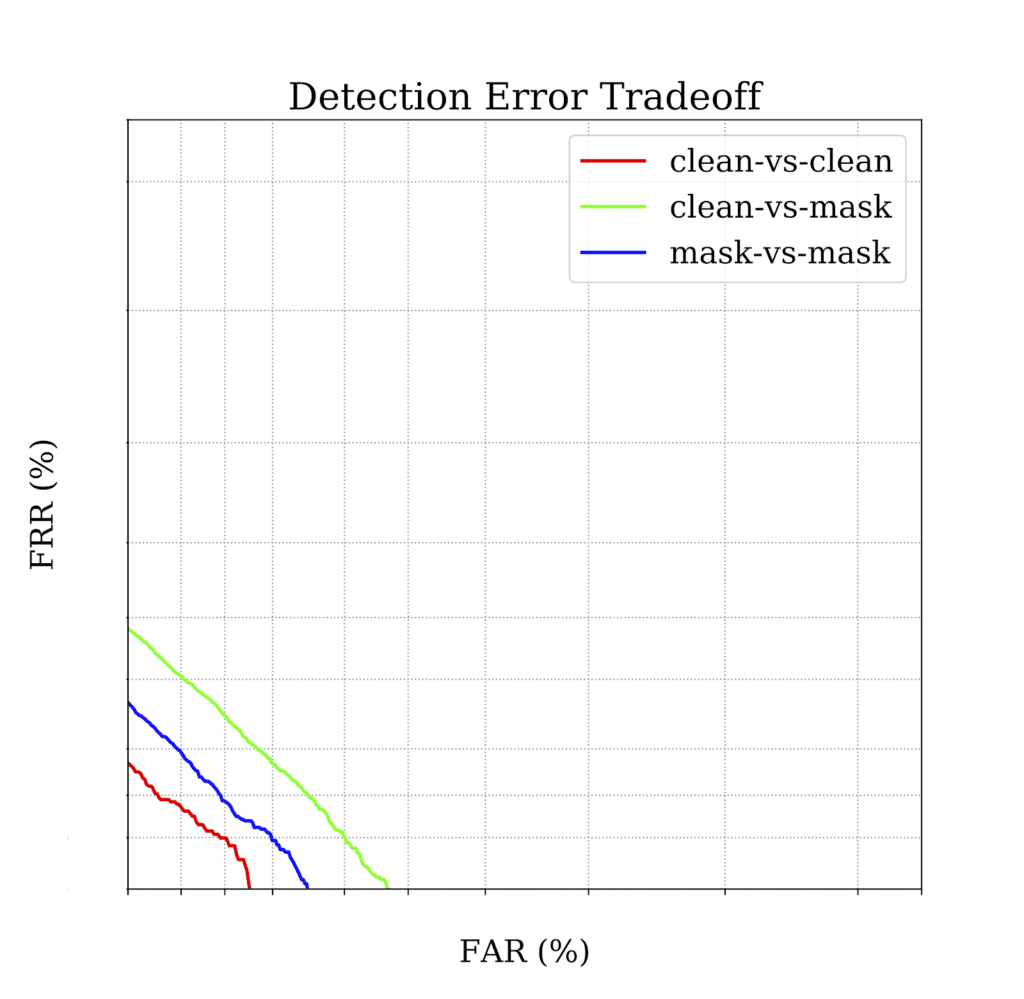

For evaluation, five phrases were randomly selected for authentication enrollment, while the remaining 15 were used for testing – all regardless of gender. Three conditions were examined:

- Condition 1, Unmasked vs. Unmasked – Both enrollment and testing are done without wearing a mask.

- Condition 2, Masked vs. Masked – Both enrollment and testing are done while wearing a mask.

- Condition 3, Unmasked vs. Masked – Enrollment is done without wearing a mask, while testing is done with a mask.

What We Found – Masks Can’t Hide a Voice

What we found closely represents what we were experiencing in our sandbox environment in the video above. The equal error rate (ERR), which describes the overall accuracy of a biometric system by measuring false acceptance rates (FAR) and false rejection rates (FRR) of authentication, slightly increased when a participant was wearing a mask during authentication time, but didn’t when they enrolled. That said, the increase was very limited, with less than a 1% increase in EER. These results suggest that wearing a mask has very little impact on the operationalization of a voice biometric solution, and a feasible alternative to face recognition, which requires easing security (i.e. failing fast) due to the failure rate of the technology

Masks Do Weaken the Voice Signal

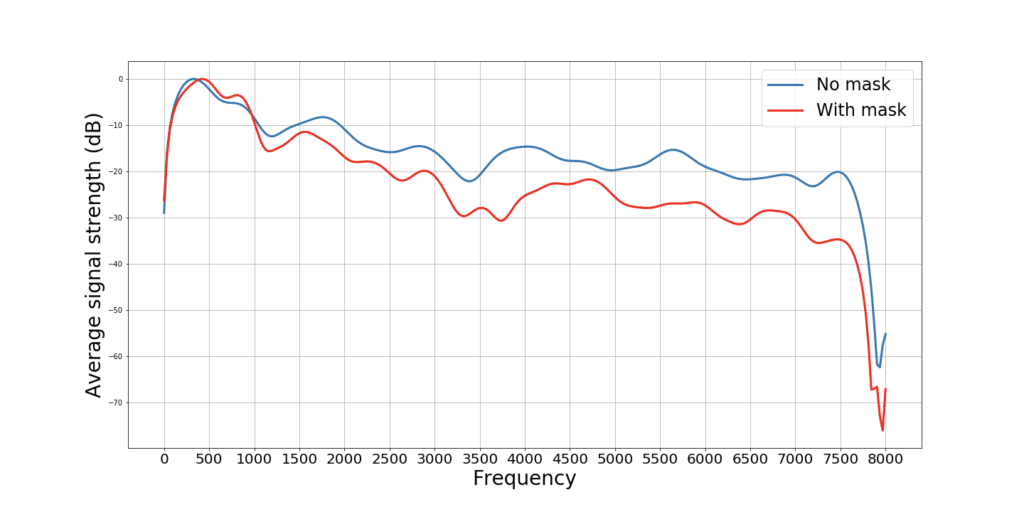

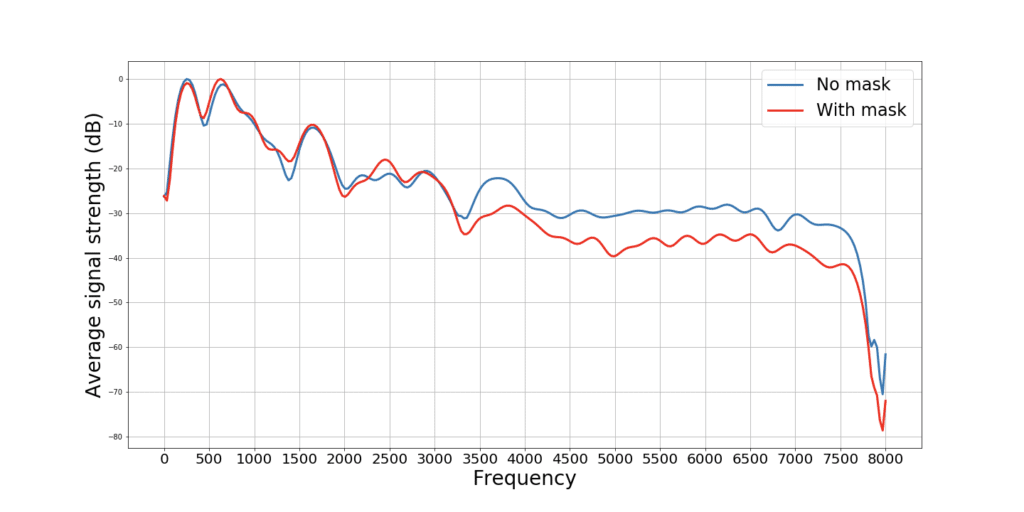

With the 100 participants in the study trying on different types of masks, it was also interesting to see how the voice signal changed depending on the type of mask used. While we’ve already pointed out that masks have very little impact on the accuracy of voice authentication, it is interesting to observe the impacts of speech when wearing different types of masks. These observations can be heard by the human ear when you’re speaking with someone with and without a mask.

For example, the voice spectrum of a female speaker wearing a DIY cloth mask weakened the voice signal above 1000Hz by 6-10dB compared to when the participant had no mask (similar impact on male speakers over 2500Hz).

What this means is that every time a word is spoken in a higher frequency (e.g. fricatives, for example “f” and “s”), it’s naturally harder to understand someone when they’re speaking.

What’s more interesting is that DIY masks impact your voice more than an N95 mask. The voice spectrum of a female speaker wearing a surgical mask weakened the voice signal above 3200Hz by 4-6dB compared to when the participant had no mask.

Similarly, the voice spectrum of a male speaker wearing an N95 mask weakened the voice signal progressively beginning from 1000Hz onwards compared to when the participant had no mask.

While different mask types devalue voice signals to different extents, the devaluation is not substantial enough to mask the identity of the speaker.

Taking This a Step Further

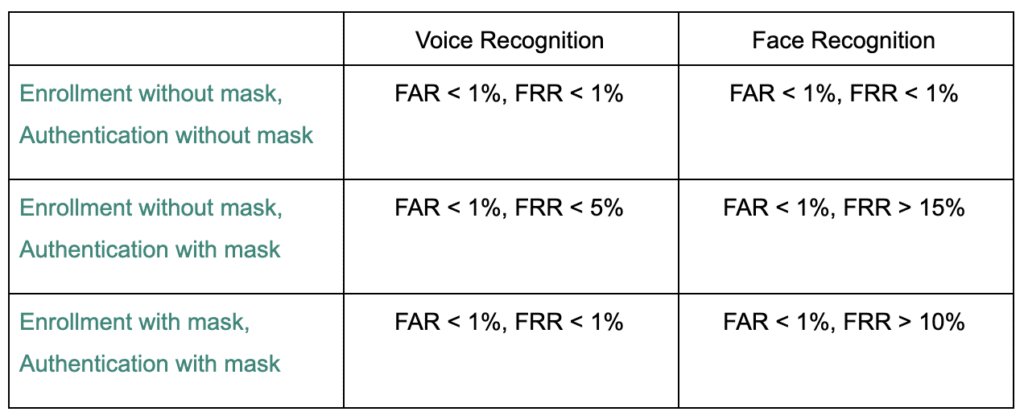

To take this a step further, we thought it would be an interesting experiment to take a single dataset to observe the performance impact of wearing a mask between voice and face authentication systems. So in a second test, we compared voice recognition and facial recognition on 100 speakers on Youtube.

If we keep the false acceptance rate fixed, the probability that the system incorrectly authenticates a non-authorized person, we can observe the false rejection rate, the probability that the system incorrectly rejects access to an authorized person. This allows us to observe the overall impact to the customer experience (e.g. how often will voice or face fail and prompt a retry) while maintaining some level of security to keep intruders out.

The results are as follows:

The findings of the research are clear: What This All Means

The findings of the research are clear:

- Voice is an authentication medium that handles the transition to the post COVID-19 world. Consumers will emerge from their homes unnerved: voice authentication will be a low-stress and reliable way to access devices, whether it’s the entrance at their office building or logging on to their banking account.

- The performance characteristics of voice biometrics significantly outperform facial recognition with the introduction of face masks.

Of course, all this technology existed before the pandemic began. Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant and Apple’s Siri have been around for the better part of a decade. But just as COVID-19 shoved Zoom from a niche application into the mainstream of national consciousness, the pandemic may do the same for touchless technologies that are more resilient to the new normal. The interesting part will be what comes next: if tech giants – including Zoom – can integrate voice assistants into daily workflow for authentication and security we may see a shift in work tech to match the shift in work-from-home patterns.